Blog

Canada’s agri-food trade and the prospect of increased protectionism

Sebastien Pouliot, Ph.D.Series: Agriculture

Tags: trade, export, import, food, agriculture, protectionism

Last week, a group of four United States representatives announced the launch of the bipartisan Congressional Agricultural Trade Caucus. The stated objective of the caucus is to advance and promote policies vital to U.S. agriculture, including boosting agricultural exports, facilitating food and agriculture trade, and knocking down unnecessary trade barriers.

Recent trends in US agricultural trade motivated the creation of the caucus. The figure below from the Economic Research Service (ERS) of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) shows that the United States has historically been a net exporter of agricultural products. The situation changed about around 2019 when the US recorded a first trade deficit for agricultural products. The USDA forecasts the US agricultural trade deficit to increase in 2024.

Figure 1: US agricultural trade between 2001 and 2023 (USDA ERS)

The question for Canada is whether the launch of a new caucus focusing on agricultural trade and the increasing US agricultural trade deficit will lead to increased protectionism. We can also ask a similar question for other countries, especially European Union (EU) countries given the recent farmer protests. Besides, the UK recently pulled out of trade negotiations with Canada. Agri-food trade has liberalized over the last three decades but there appears to be growing pressures for protectionism, or, at the least, less willingness to further liberalize agri-food trade.

Given this, I think it’s worth examining Canada’s agri-food trade data. I’ll take a gander at agri-food trade balance, and describe trade by country and by commodity. I’ll conclude by reflecting on the prospect of increased protectionism and how it could manifest for Canada’s exports. If you are not interested by the trade data, you can jump to the last section for my thoughts about the possibility of increased protectionism.

Agri-food trade

Published in 2018, the Report of Canada’s Economic Strategy Tables: Agri-food sets a target of CAD 85 billion for agri-food exports by 2025. Canada’s exports surpassed the target early with agri-food exports totalling CAD 93.9 billion in 2022.1 Agri-food exports were CAD 99.9 billion in 2023. A major factor explaining that success is price inflation for agri-food products.

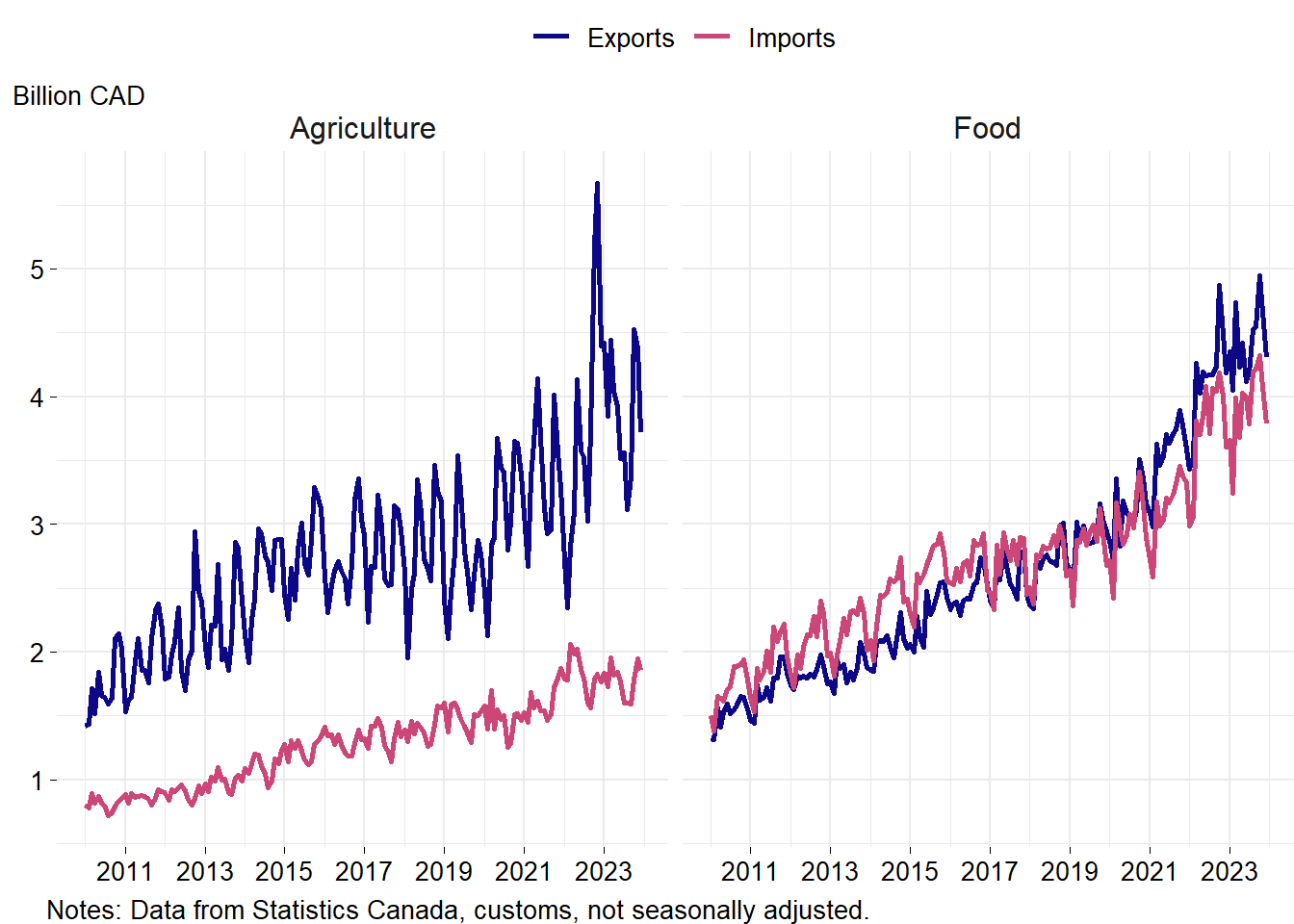

Figure 2 shows Canada’s monthly agri-food trade between 2010 and 2023. Exports, imports for both agriculture and food have been trending up and are highly seasonal. Exports of agricultural products largely surpass imports. In 2023, Canada exported on average CAD 3.9 billion and imported CAD 1.8 billion per month of agricultural products. The agricultural trade surplus was CAD 25.6 billion in 2023.

Food exports and imports are comparable in value. Food imports exceeded exports until 2019 when Canada became of net food exporter. Canada returned to a negative food trade balance in 2020 but since 2021 Canada has been a net food exporter. In 2023, Canada exported on average CAD 4.4 billion and imported CAD 3.9 billion per month of food. The food trade surplus was CAD 6.1 billion in 2023.

Figure 2: Canada monthly agri-food trade

Trade by country

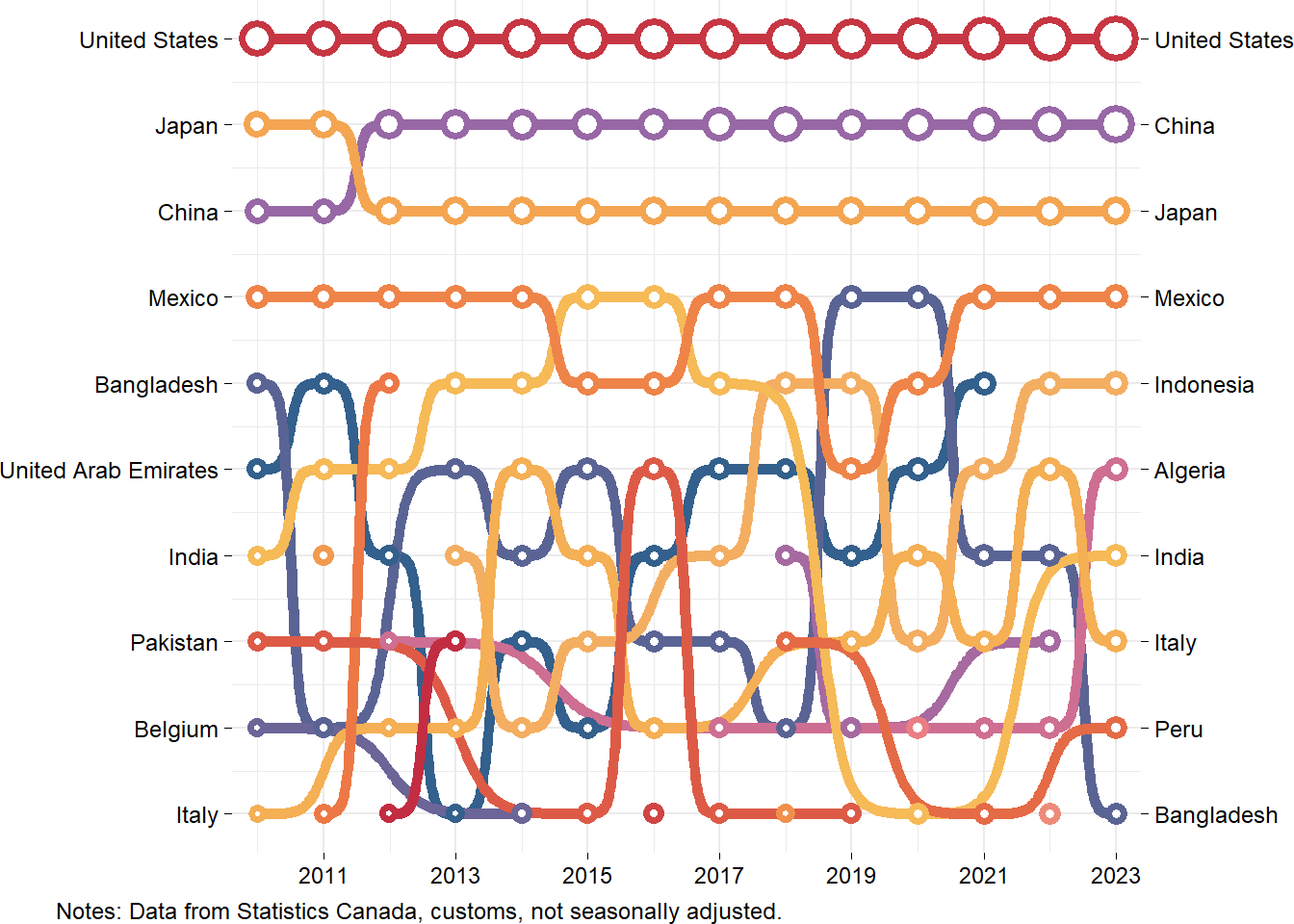

Let’s now examine who are Canada’s main agri-food trading partners. I will use bump charts to show Canada’s top ten trading partners over time. The charts show at the top Canada’s number one partner and at the bottom Canada’s tenth trading partner. The charts do not show trade values but the size of the circles show the relative importance of the trade relationship, a larger circle indicating a greater value.

Agriculture

The United States is by far Canada’s main export destination for agricultural products. Japan, China and Mexico round the top four. From positions five to ten, there is no consistency with countries jumping up or down several positions from one year to the next. India, Bangladesh, and Indonesia jump in and out of the top five depending on their imports of pulses, cereals and canola.

Figure 3: Ranking of Canada's exports of agricultural products by destination country between 2010 and 2023

The ranking of Canada’s agricultural imports by origin is quite consistent. The United States is number one, Mexico number two, China number three and Chile number four. After that, it varies from year to year. Note that Thailand was ranked number five in 2010 and that it has dropped out of the top ten in 2023. Peru was out of the top ten until 2014 and it is now number four. CPTPP likely helped Peru’s exports to Canada. The main imports from Chile and Peru are edible fruits and nuts.

Figure 4: Ranking of Canada's imports of agricultural products by origin country between 2010 and 2023

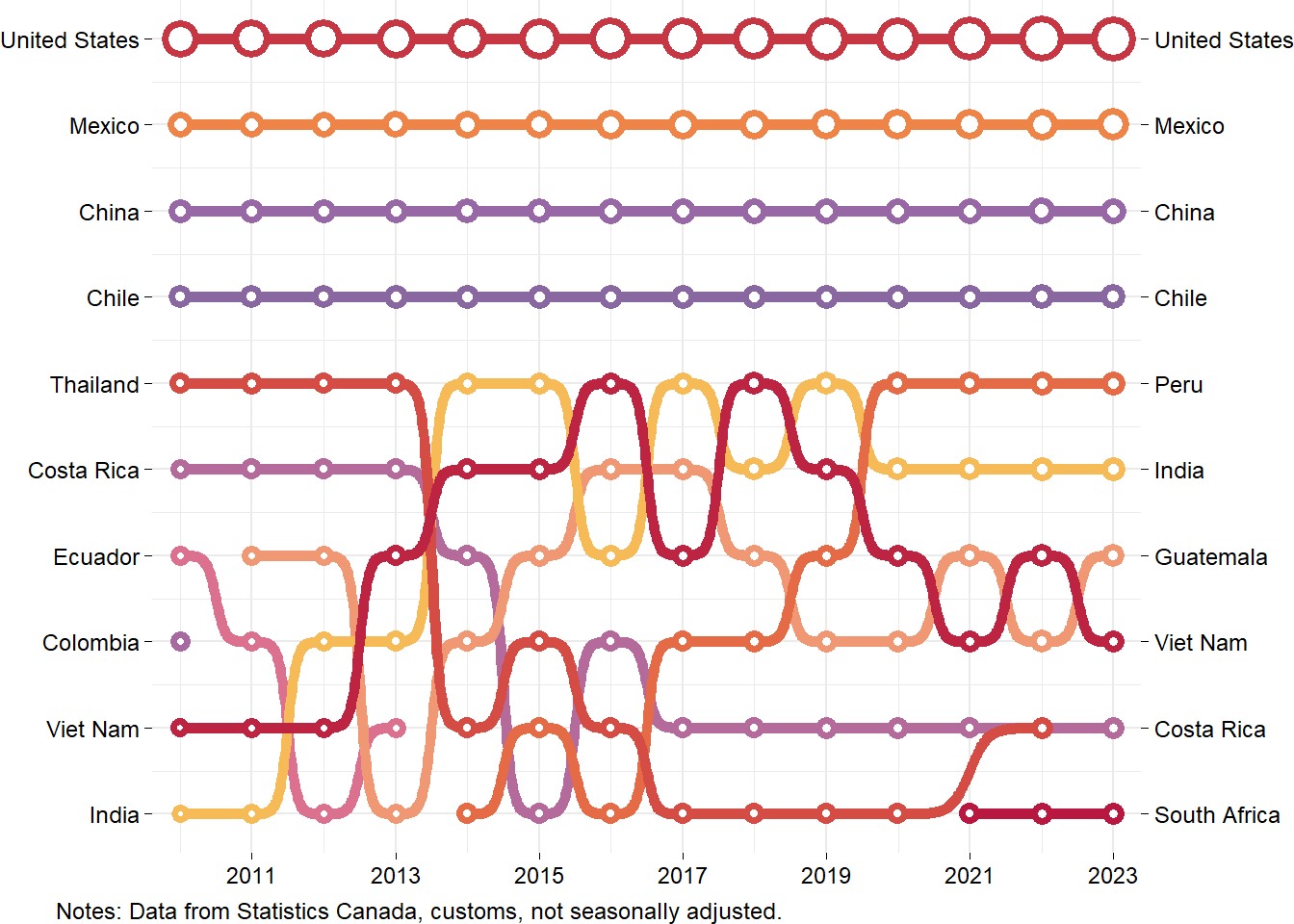

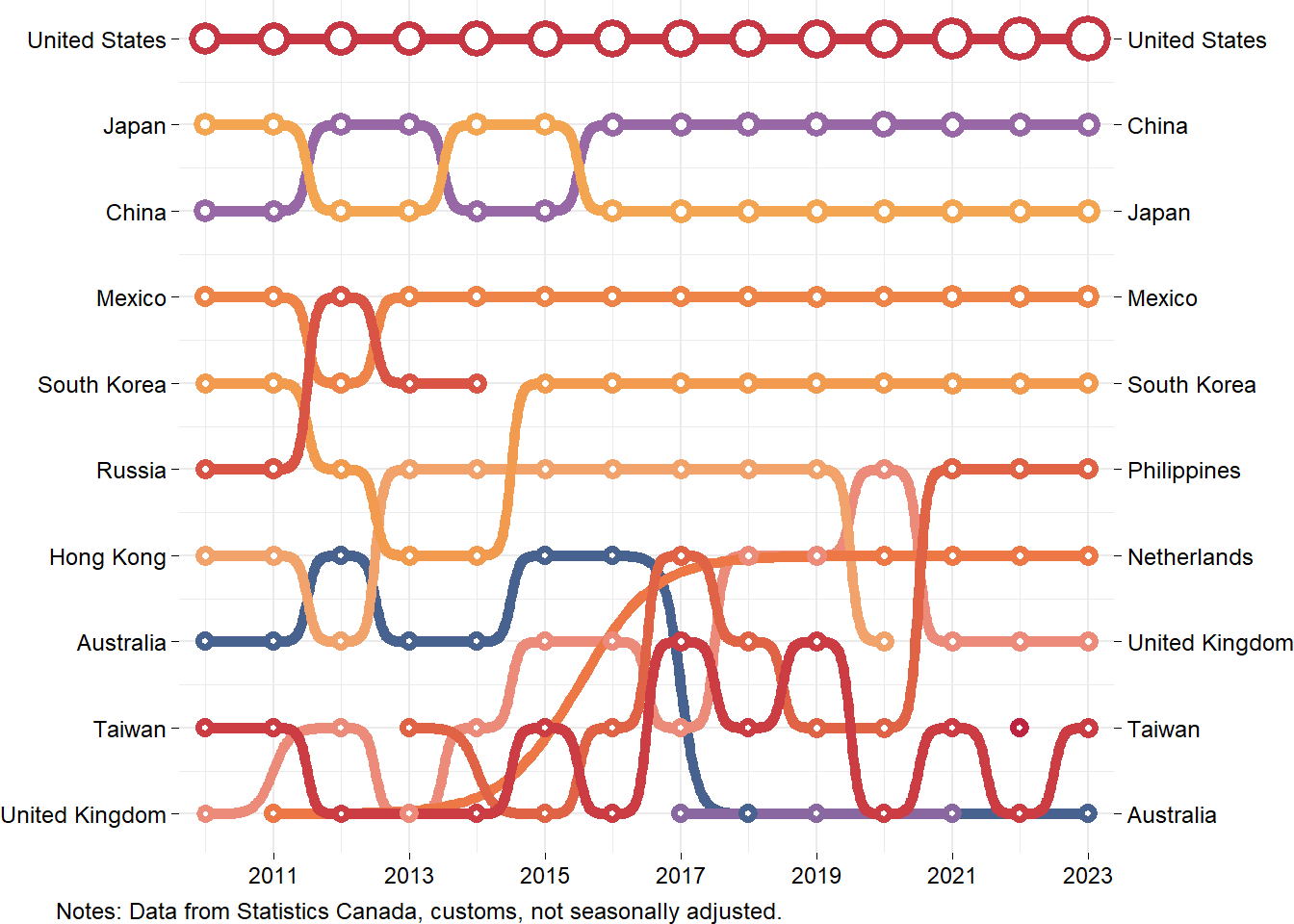

Food

Again, it’s no surprise that the United States is the main destination, and by far, for Canada’s food exports. China, Japan, Mexico and South Korea, follow in that order since 2016. The Philippines, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom have ranked sixth, seventh and eighth in the last three years.

Figure 5: Ranking of Canada's exports of food by destination country between 2010 and 2023

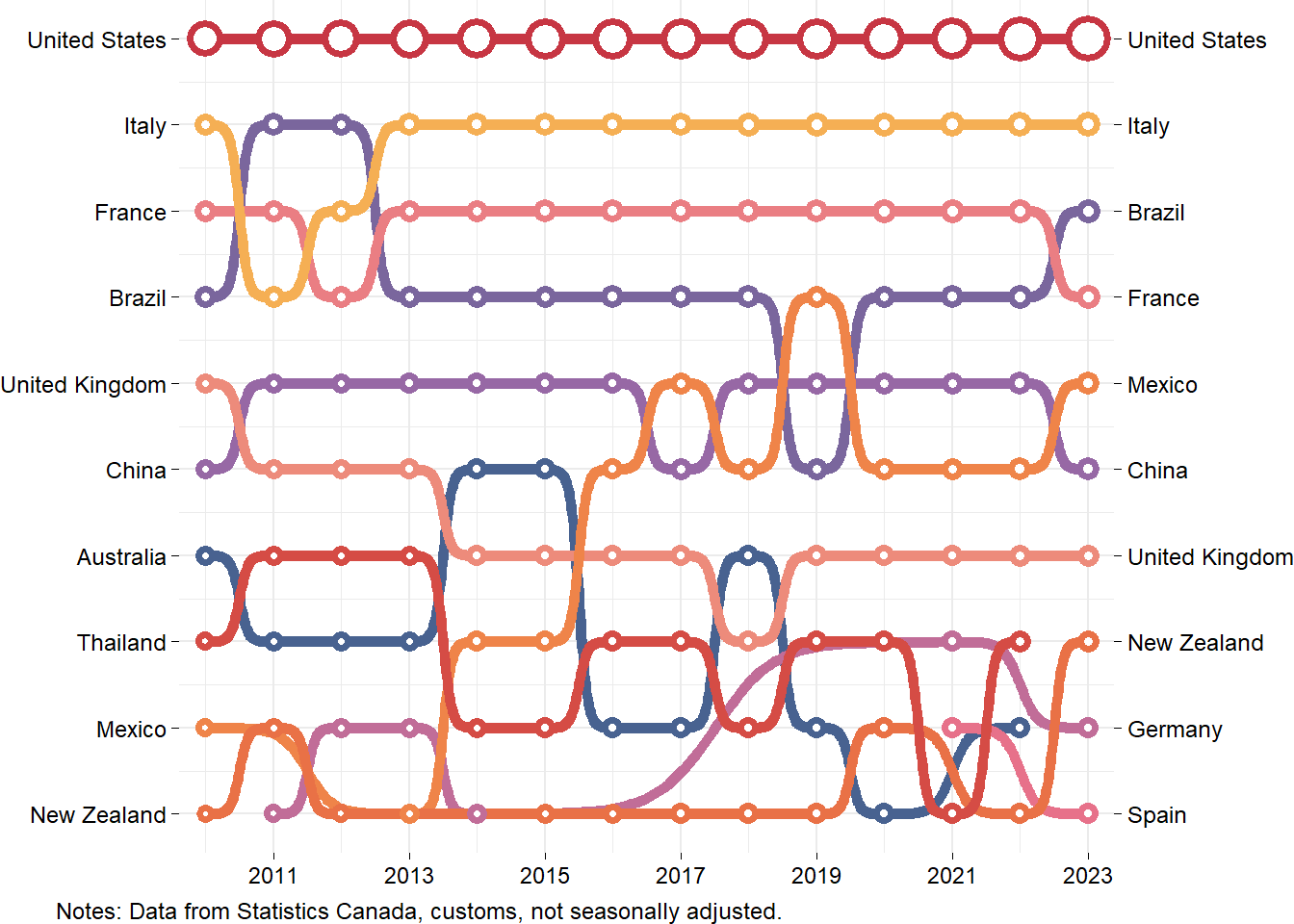

The United States is again the main trading partner when examining food imports. Then the list of countries is quite different from the previous charts. Italy has been number two since 2013. Brazil stole in 2023 the number three position from France, who dropped to number four. Mexico is in fifth position followed by China and then by the United Kingdom who has not been lower than in seventh position except in 2018 when it fell to number eight.

Figure 6: Ranking of Canada's imports of food by origin country between 2010 and 2023

Trade by commodity

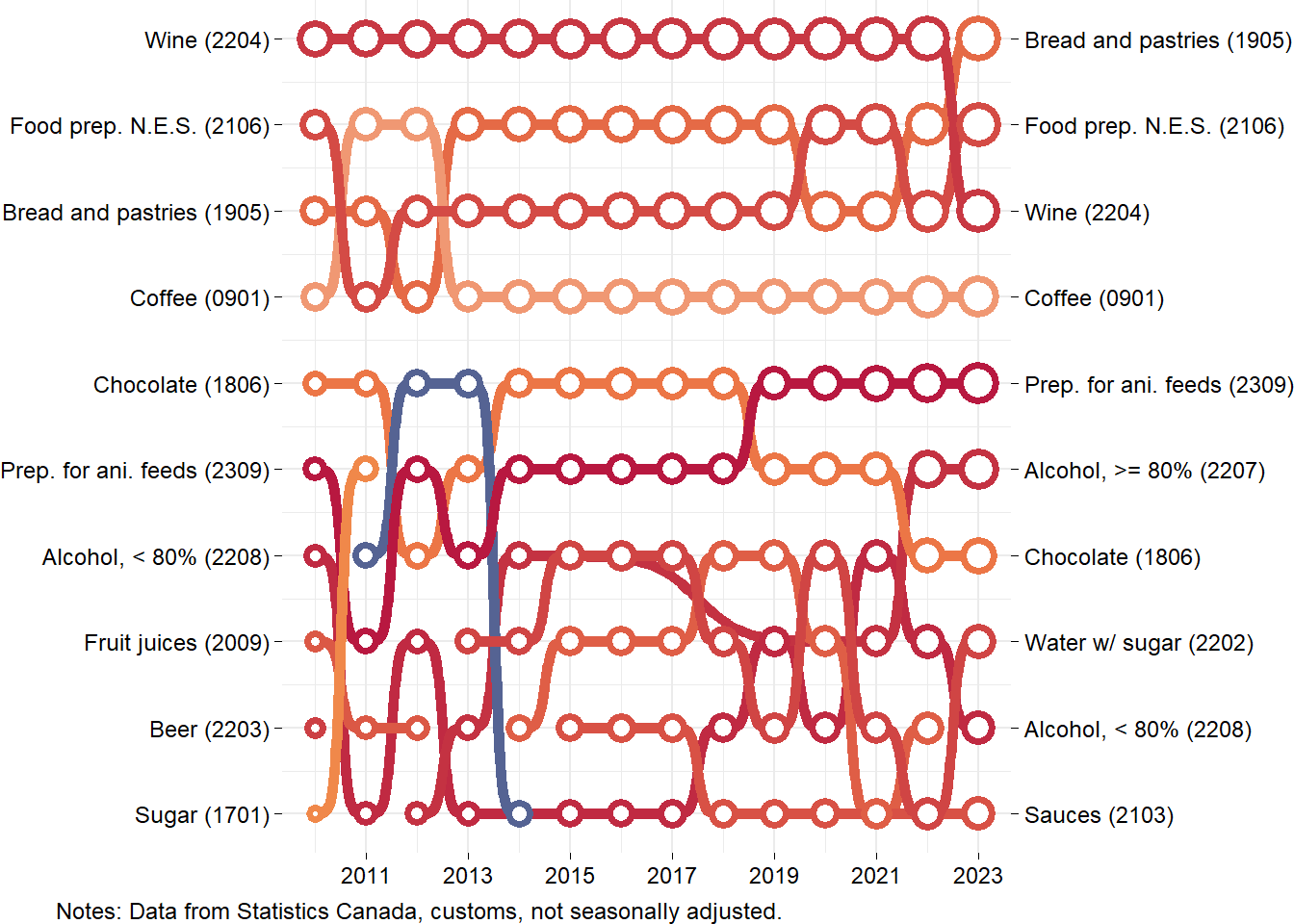

I also show rankings for agri-food trade by commodities using bump charts. The top traded commodity is at the top and the size of the circles shows the relative value of trade.

In the figures below, I include the HS4 code in the shortened product descriptions to avoid confusion. You can verify product classification at this page.

Agriculture

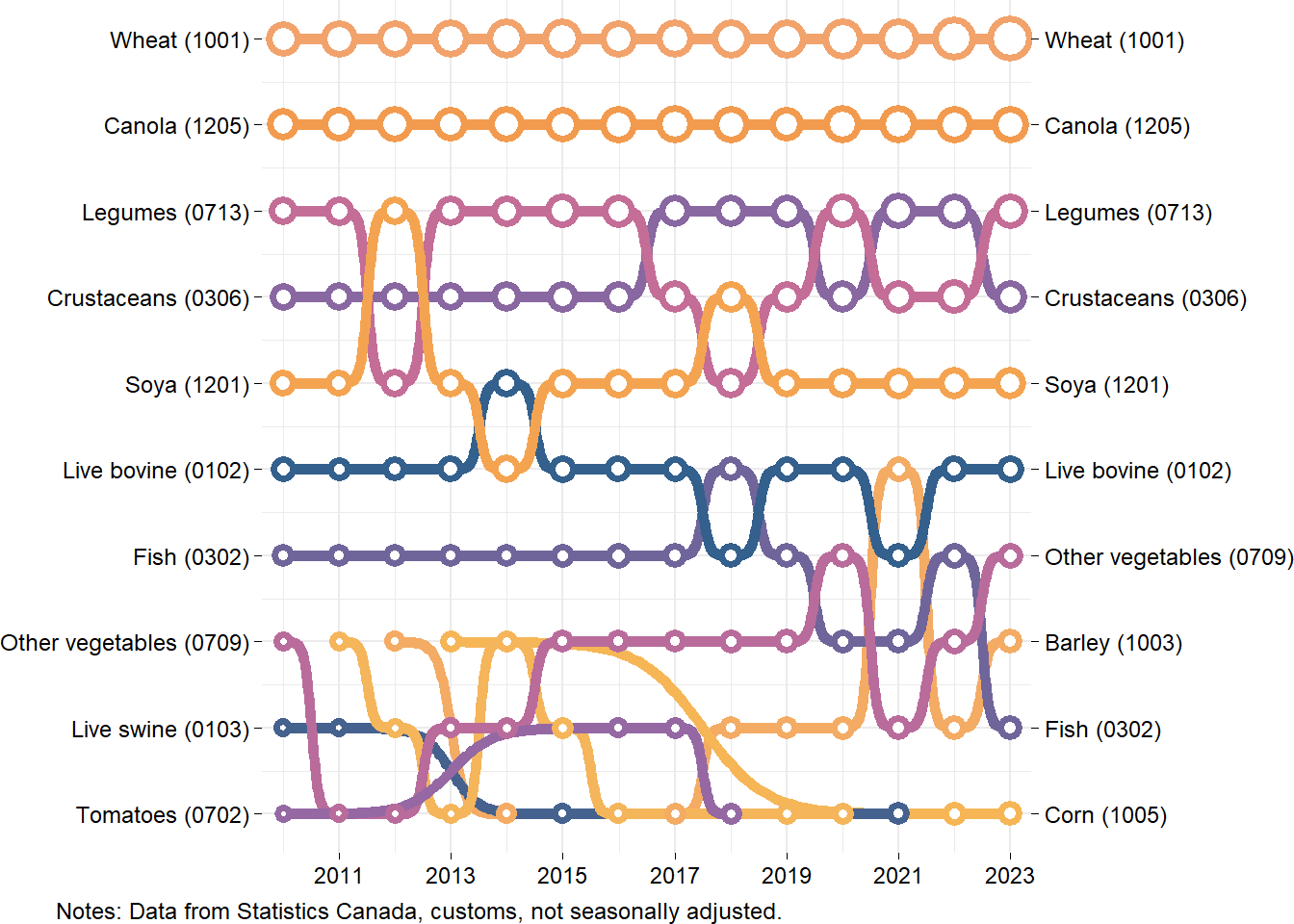

Prairies crops dominate the ranking of Canada’s exports of agricultural commodities. Wheat is number one, followed by canola. In third are legumes, who often trade position with crustaceans. Soya is in fifth position since 2019. Live bovine is in sixth but occupied a higher spot before 2010. Live bovine exports to the United States have declined and have stayed lower since the United States adopted mandatory Country of Origin Labelling (m-COOL) for red meat in 2008, even though the dispute was resolved in 2015.

Figure 7: Ranking of Canada's agricultural exports by product between 2010 and 2023

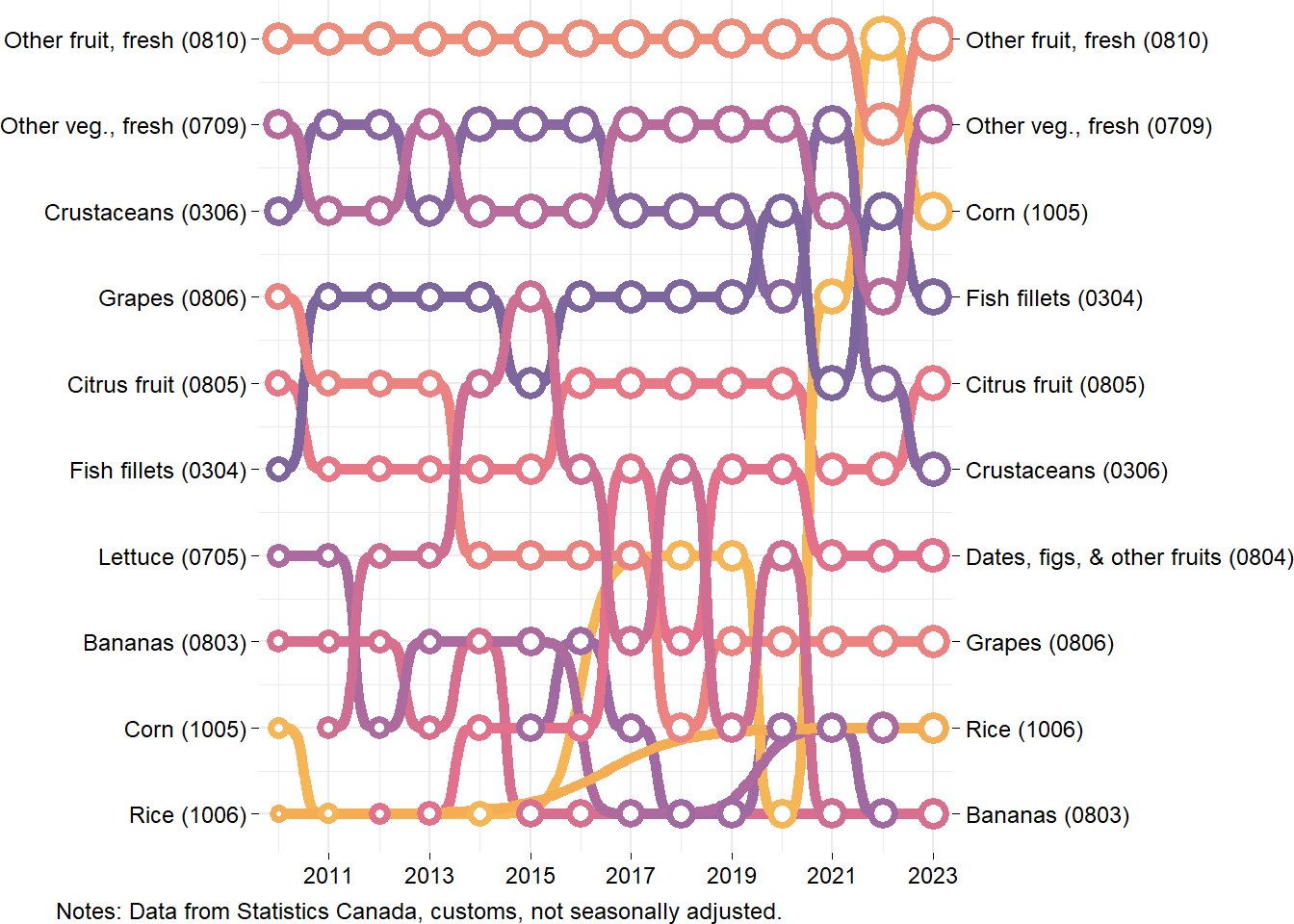

Not too surprisingly for a northern country, Canada’s two main agricultural imports are fresh fruits and vegetables. The ranking of Canada’s agricultural imports tends to vary significantly from year to year depending on commodity prices. The top ten includes several products that are not grown, or grown in small quantities, in Canada like bananas, citrus, rice and grapes. Observe the recent rise of corn imports in the ranking following the drought in the Prairies in 2021.

Figure 8: Ranking of Canada's agricultural imports by product between 2010 and 2023

Food

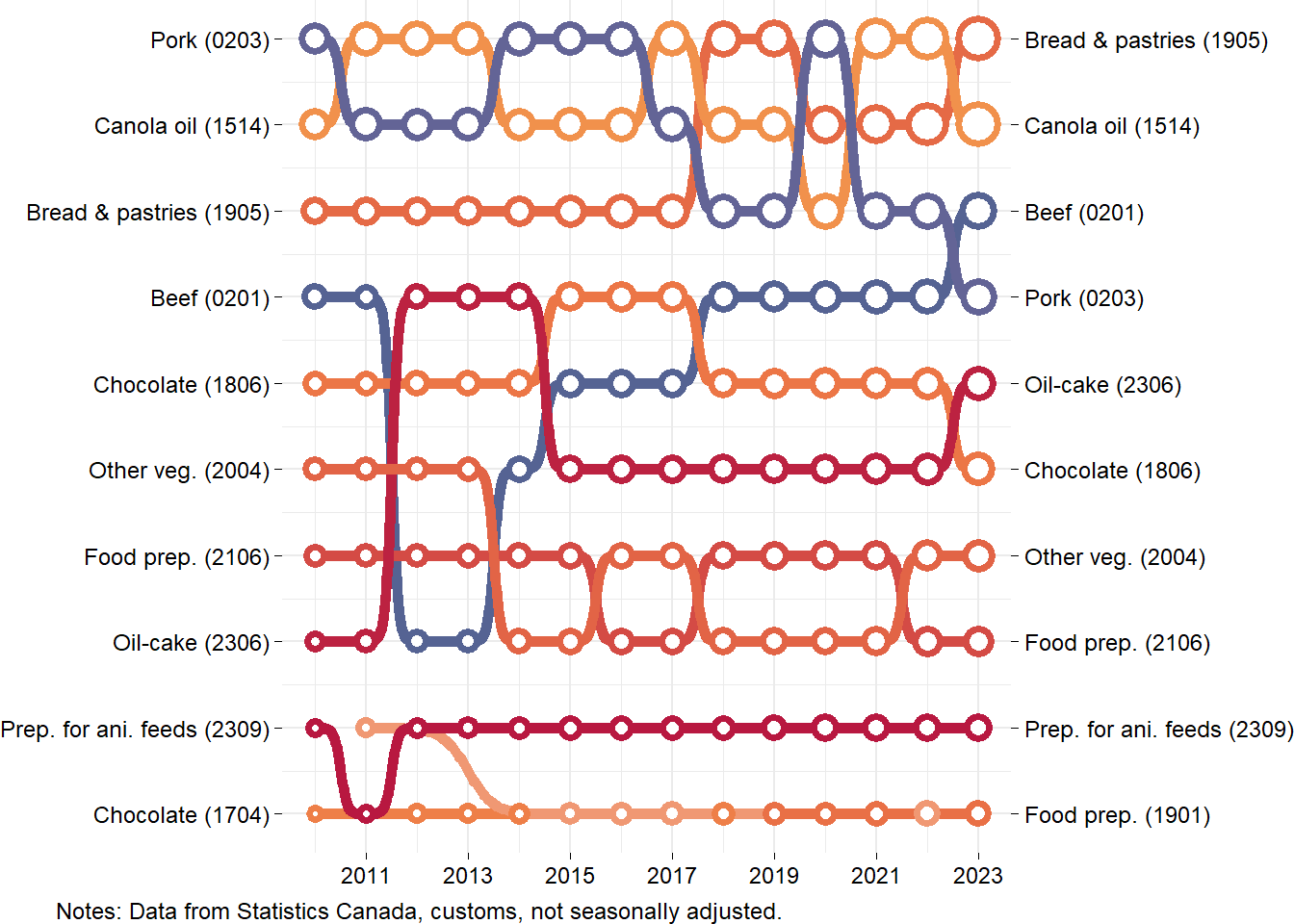

The products occupying the top four of Canada’s food exports tend to trade positions: bread and pastries, canola oil, beef, and pork. In the case of bread and pastries, it’s a bit of mystery to me as I do not know the comparative advantage that explains strong exports of bread and pastries by Canada (wheat production?). Moreover, Canada is also a strong importer of bread and pastries, although exports largely exceed imports. In the case of chocolate products, who are consistently among the top ten food exports, although Canada does not produce cocoa, lower sugar prices in Canada compared to the United States makes Canadian firms competitive on the US market.

Recent lower pork prices have caused pork to fall to number four. On the opposite, with higher prices from droughts in the US and Canada, beef has climbed to the third spot in 2023.

Figure 9: Ranking of Canada's food exports by product between 2010 and 2023

Food imports include several specialty products like wine, coffee, and certain alcohols. Bread and pastries occupy the top position, just like in the case of exports. Two-way trade also occurs for preparations for animal feeds and for chocolate. Quite obviously, Canadians like imported alcoolique beverages.

Figure 10: Ranking of Canada's food imports by product between 2010 and 2023

Are we going to see increased protectionism and in what form?

Whether we will see more protectionism depends on a few factors, including:

- Political situation: we will see more protectionism depending on who gets elected in the United States in November and likewise in the next rounds of elections elsewhere in the world. The new caucus in the US House of Representatives could also lead to increased protectionism.

- Agri-food prices: When farming and producing food is profitable, the impetus for protectionism is much lower. The USDA recently forecasted net farm income to decline by 25.5% in 2024. If this forecast materializes, this could lead to increased pressures for protectionism in the United States.

- Protests in Europe: We expect changes to come after the protests that rocked several European countries since January. That could include increased farm support but also increased protectionism.

The figures above show the obvious fact that the United States is Canada’s main agri-food trade partner. This depency on the US market has its risks. What could we expect from the United States if it moves to increase protection of its agri-food sector?

- Tariffs: Former President Trump stated that he would impose tariffs on all imported goods if re-elected. This, it appears, would not exclude Canada and agri-food products and would essentially mean the end of free trade with the United States.

- Return of m-COOL for red meat: Since the US lost at the WTO against Canada and Mexico regarding m-COOL for red meat, steps are occasionally taken for its return. Currently, profitability is low in the hog sector but is high in the cattle sector. I would not be surprised if we see increased pressure to reinstate m-COOL once profitability in the cattle sector declines.

- Measures regarding milk: In the second round of the dairy dispute between Canada and the United States, the CUSMA panel sided with Canada. In reaction to the decision, Ambassador Katherine Tai stated We will continue to work to address this issue with Canada, and we will not hesitate to use all available tools to enforce our trade agreements and ensure that U.S. workers, farmers, manufacturers, and exporters receive the full benefits of the USMCA. This quote leaves open the possibility that the United States could take measures against Canada’s dairy sector even though the panel sided with Canada.

Canada’s agri-food export portfolio comprises a large number of countries and products. If any country importing Canada’s agri-food restricts imports, this may result in non-negligible economic impacts to Canadian agri-food sectors. It’s hard for me to guess how import restrictions by countries other than the United States could manifest. Based on recent history, I cannot rule out that China could impose restrictions on the import of certain commodities as it had done for canola and pork a few years ago. However, I cannot predict if, when, and how such restrictions could be imposed. India imposes tariffs on pulses depending on domestic prices. In December, it temporarily removed a 50% tariff on the import of pulses. The tariff is set to come back on March 31st 2024.

Canada’s trading partners will continue to put pressure for market access in sectors under supply management. Recent trade agreements have maintained supply management systems but weakened them by increasing access to Canada’s domestic market. Country members of these agreements may challenge Canada’s TRQ administration, event though economic factors explain why they are unfilled. Recent examples include challenges for dairy TRQs by the US under CUSMA and by New Zealand under CPTPP. Although these challenges are not protectionnism measures, there can be a cause for concern. We will see if the door is now open for more challenges.

-

I use HS chapters 1,3,6,7,8,10,12 for agriculture and HS chapters 2,4,9,11,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,35 for food. This should closely match with the set of chapters used by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. ↩︎