Blog

The impacts of 25% US tariffs on the Canadian hog and pork industry

Sebastien Pouliot, Ph.D.Series: Agriculture

The United States postponed tariffs on Canadian and Mexican imports until March. These tariffs, and the retaliatory tariffs that would have accompanied them, would have had broad impacts on North American economies. No one knows what will happen in March and the threat of a tariff war remains.

In this blog post, I examine the impacts of US tariffs on the Canadian hog and pork industry. We will see that the United States is an important destination for Canadian hog and pork and that the tariff would have a major impact on the Canadian hog and pork industry.

Canadian exports of hogs and pork

Canada exports feeder pigs and fed hogs to the United States. The trade data allow us to distinguish by classifying feeder pigs as those that weigh less than 50 kg and fed hogs as those that weigh 50 kg or more. Manitoba is the largest exporter of feeder pigs, mostly from the export to the United States of weanlings weighing less than 7 kg. Ontario exports the most fed pigs to the United States.

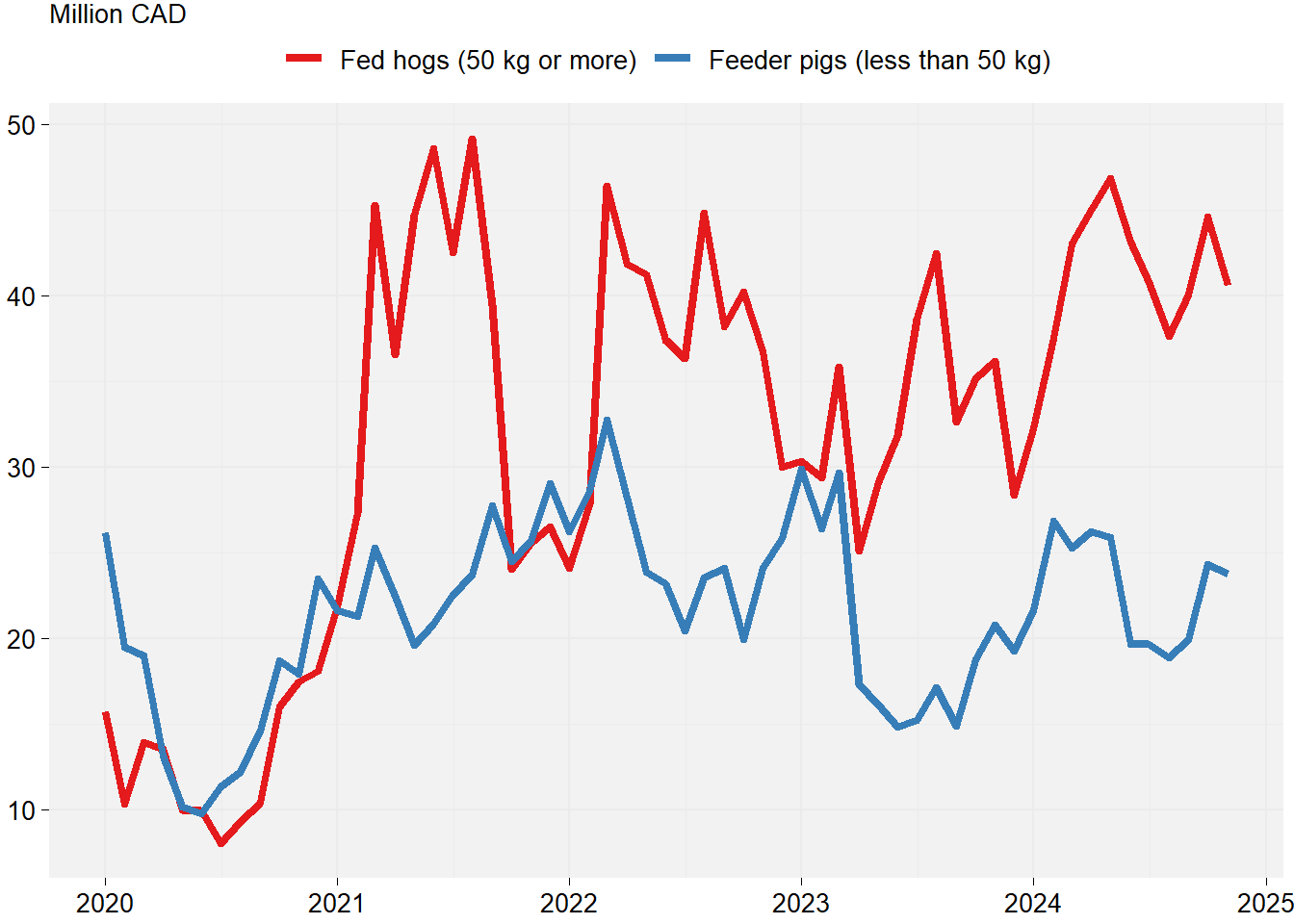

Figure 1 shows monthly Canadian exports of live pigs to the United States since 2020. Exports of fed pigs are seasonal but have been relatively stable since 2001 on an annual level. Likewise, exports of feeder pigs have been holding fairly steady.

Figure 1: Monthly Canadian hog exports to the United States

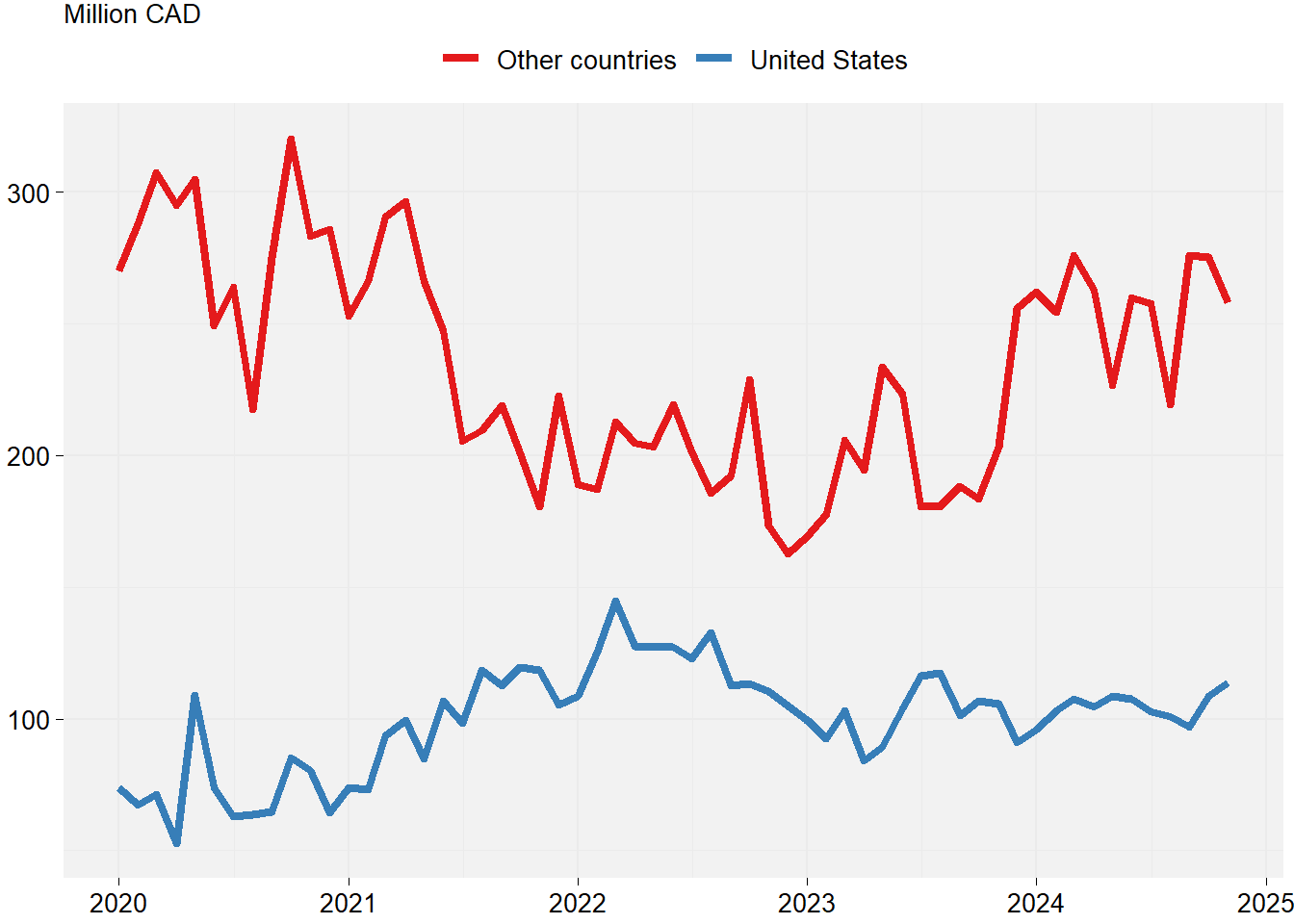

Figure 2 shows monthly Canadian exports of pork to the United States and to other countries. In 2020 and 2021, exports to other countries were boosted by the outbreak of African swine fever in China. China’s hog inventory has since recovered and the global demand has diminished. Pork exports to the United States are about a quarter of Canada’s total, and have been holding steady.

Figure 2: Monthly Canadian pork exports

Estimates of the economic impacts

I use an equilibrium displacement model, a type of model that has been used before to study livestock and meat trade between Canada and the United States (see for example, Brester, Marsh and Atwood (2004), Pendell, Brester, Schroeder, Dhuyvetter and Tonsor (2010) or Hahn, Sydow and Preston (2019)).

I modelled the supply chains in Canada and the United States, starting with feeder pigs (weanlings), then fed hogs that are slaughtered to produce pork that is sold at wholesale and then at retail. I specifically consider Manitoba weanlings meant for export to the United States. Canadian fed hogs are either slaughtered domestically or are exported to the United States. Pork produced in Canada is either consumed domestically, exported to the United States or exported to other countries. I do not consider the impacts of tariffs on feed costs and on the costs for other inputs.

I did my best to calibrate the model to 2024 data. This was not always easy. Calibration to 2024 data means that the model takes the economic conditions observed in 2024 and then examines the impact of 25% tariffs on US imports of feeder pigs, fed hogs and pork, everything else remaining the same. The results cannot be interpreted as a prediction of what would happen is 25% tariffs were applied in 2025. The economic conditions in 2025 are different; notably, the Canadian dollar is weaker. More on that below. Nonetheless, the model gives a good idea of the size of the economic impacts that can be expected in 2025.

Scenario 1: Canadian fed hog prices adjust according to supply and demand conditions

Quebec and Ontario price fed hogs according to formula calibrated to prices in the United States. In this first scenario, I consider that fed hog prices adjust according to supply and demand conditions. In the next section, I will consider that Quebec and Ontario keep their pricing formulas as they currently apply.

Table 1 shows the impacts of the tariffs on the Canadian hog and pork industry. The value of feeder pig exports to the United States drop by more than 50% from an 18% drop in the export price and a 36% decline in the export volume. The price of hog carcass (i.e., fed hogs) declines by 7% and production declines modestly by 1%, yielding an 8% decrease in the value of fed hog production. Exports of fed hogs and pork to the United States completely stop. Export of pork to other countries increase by 28% to exceed one billion kg and approach CAD 3.8 billion. The price at wholesale drops by 4.7% because there is more pork is sold domestically, causing a 2% decline in pork prices at retail. This means that Canadian prok consumers gain from the US tariffs.

Scenario 2: Quebec and Ontario hog pricing formulas do not change

This second scenario assumes that Quebec and Ontario keep their hog pricing formulas. That is, hog carcass prices are still calibrated to US prices, even though Canada does not export fed hogs and pork to the United States because of the 25% tariffs. I make that assumption for all fed hogs in Canada, although they are priced differently in provinces other than Quebec and Ontario.

The impacts on feeder pig exports are the same as in scenario 1. Feeder pig exported to the United States from Manitoba are grown for export and there would be limited capacity to grow and slaughter them in Canada.

Table 2 shows the results for scenario 2. The price of hog carcass increases by 2%. This is from the US reference price increasing because of lower supplies from the loss of imports from Canada. As a result of a higher price, fed hog production increases by 0.4% in Canada. Export volume to other countries increases by 53%, while value increases by 43%. The price of pork at wholesale declines by 9.0% and the price at retail declines by 4.5% because of stronger supplies in Canada compared to scenario 1.

This scenario is, in practice, not feasible because processors’s margins get squeezed by a higher price for hog carcass and a lower price for pork at wholesale. If the price formulas are maintained in Quebec and Ontario, something else will have to give. One possible solution is production cuts that would cause wholesale prices to increase enough for processors to maintain positive margins. Still, processors’ profits would declines because from the lower volumes.

Lower exchange rate

My model does not consider that the Canada-US exchange rate in early 2025 is about 6% lower than it was on average in 2024. Effectively, a lower exchange rate diminishes the impacts of the tariffs. Indeed, in the past, countries have adopted monetary policies to lower their exchange rate as a strategy to get around punishing tariffs. The value of the Canadian dollar is expected to decline in response to the US tariff.

A 6% lower exchange rate means a 19% effective tariff in 2025 compared to the 2024 baseline. I calculated the impact of 19% tariffs in scenario 1. The impacts on feeder pigs are lower but for the rest of the supply chain, the impacts are the same as those in Table 1. This is because 19% tariffs are sufficient to cause exports of slaughter hogs and pork to the United States to drop to zero.

I found that a 7% drop in the exchange rate compared to 2024 would be sufficient for fed hog exports to the United States to continue, although export volumes would be much lower. For pork exports to the United States to continue, it requires about a 15% drop in the exchange rate given a 25% tariff.