Blog

Is Canada agriculture in a recession?

Sebastien Pouliot, Ph.D.Series: Agriculture

The financial health of the Canadian agricultural sector is worrisome given lower crop prices. Many ag. economists are the opinion that the US farm sector is in a recession. In this blog post, I examine whether we can make the same conclusion about the Canadian farm sector.

Defining a recession is not simple. When considering the whole economy, a technical recession is defined as two consecutive quarters with negative year-over-year growth. We could apply that definition for the farm sector by examining farm cash receipts data. However, this definition does not take into account some realities in agriculture like price volatility and the sensitivity of farm income to weather shocks.

I’m not going to define the concept of an agricultural recession. What I will do is inspect recent trends in farm prices and farm cash receipts. Farm prices tell us about the revenue per unit of production, while farm cash receipts also consider the effect of output variations. If we observe th at prices and cash receipts haven’t been growing and are not forecasted to grow, then we will conclude that an agricultural recession is likely.

Farm prices

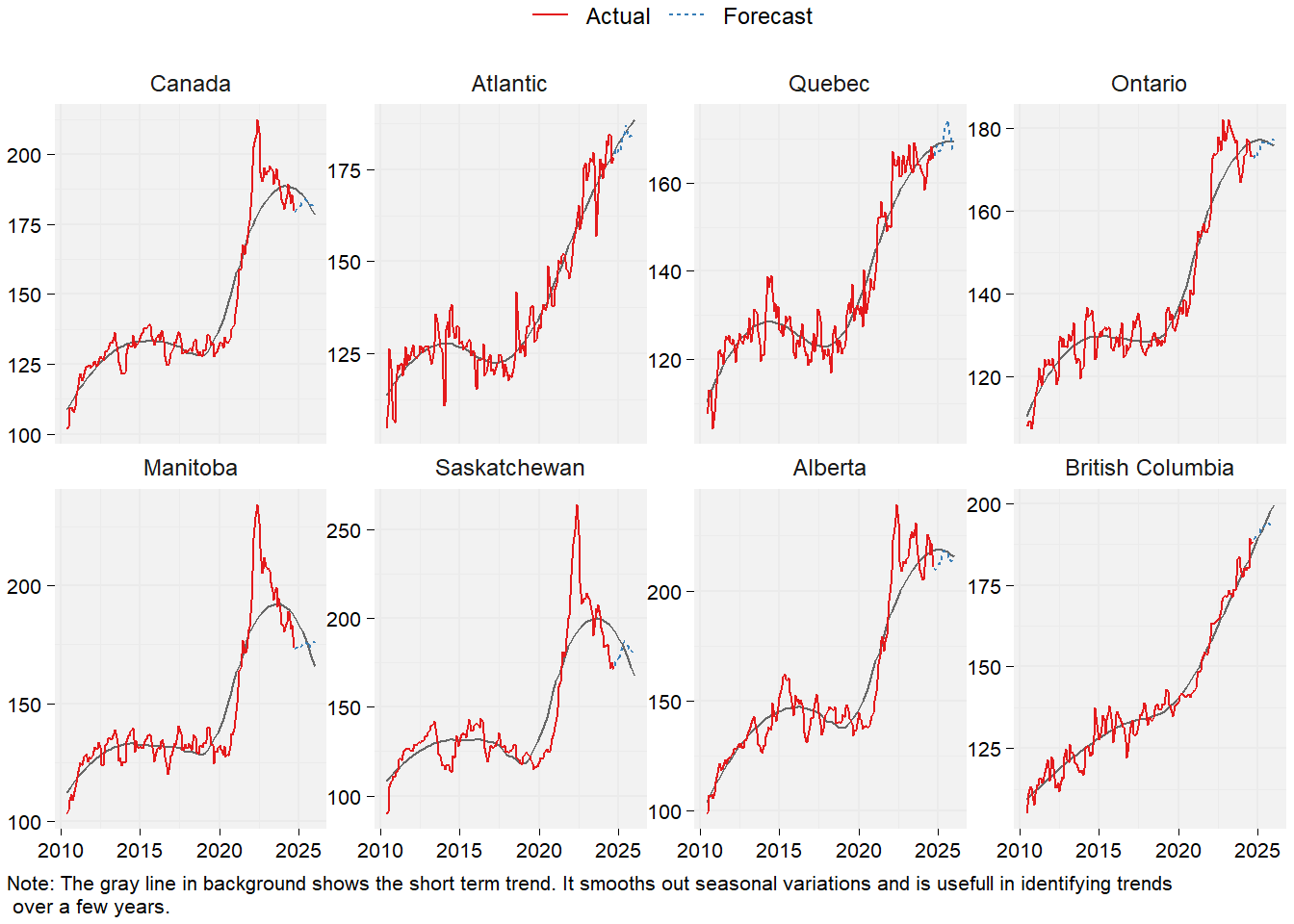

The price data are from Statistics Canada Farm product index series. I use price indexes because they allow comparisons across provinces and groups of commodities. Farm price indexes consider a representative basket of commodities in each province. This means that price indexes vary across province because economic factors specifics to them and because bundles of agricultural products are not exactly the same across provinces.

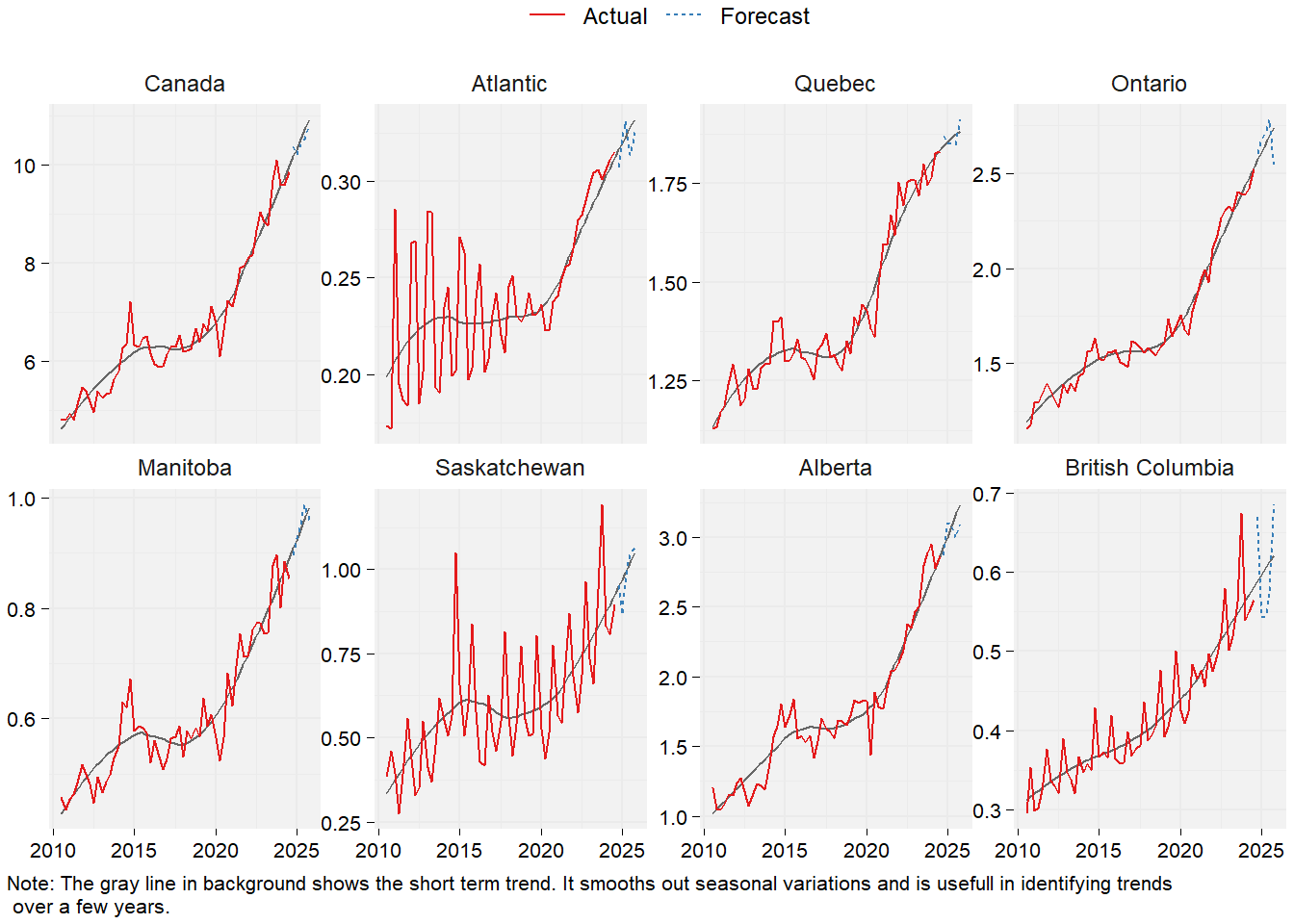

Total crop price index

For all provinces, except for the Atlantic and British Columbia, the crop price index peaked in 2022 and has trended down since. These trends follow from commodity crop prices. Forecasts do not indicate a significant potential for prices to rebound over the next year.

The size of the 2022 peak depends on each province crop mix. The Prairies are important producers of commodity crops and we observe much more prominent peaks in those provinces. In Quebec and Ontario, the peaks are smaller, as fruit and vegetable productions are relatively more important.

Figure 1: Monthly farm product price index for total crops (2007 = 100)

Total livestock and animal products price index

Livestock prices have trended upward in all provinces since 2020, but have been volatile. The forecasts show that prices are likely to peak in the middle of 2025 to then decline following seasonal patterns, most notably for hog prices.

Figure 2: Monthly farm product price index for total livestock and animal products (2007 = 100)

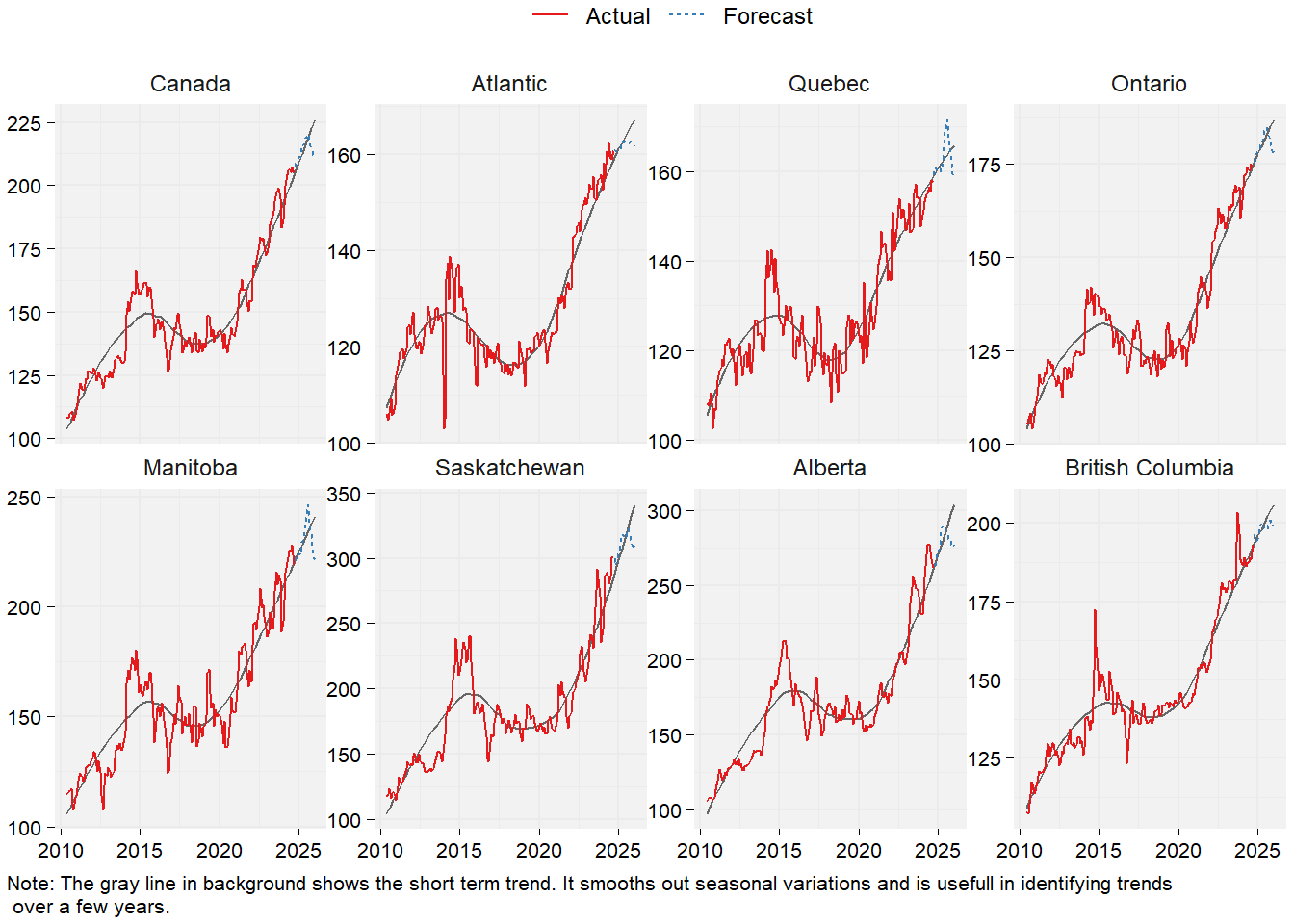

Total price index

When considering total farm price indexes, we observe that in provinces who largely depend on commodity crops, in particular Manitoba and Saskatchewan, prices peaked in 2022 and then have dropped since. The other Prairies Province, Alberta, has a large crop sector but also a large cattle sector. Prices have declined in that province but less so than Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Quebec and Ontario have diversified agriculture production and prices have stagnated since 2022, but have been volatile. For the Atlantic and British Columbia, prices have generally been trending up since 2010.

Figure 3: Monthly total farm product price index (2007 = 100)

Farm cash receipts

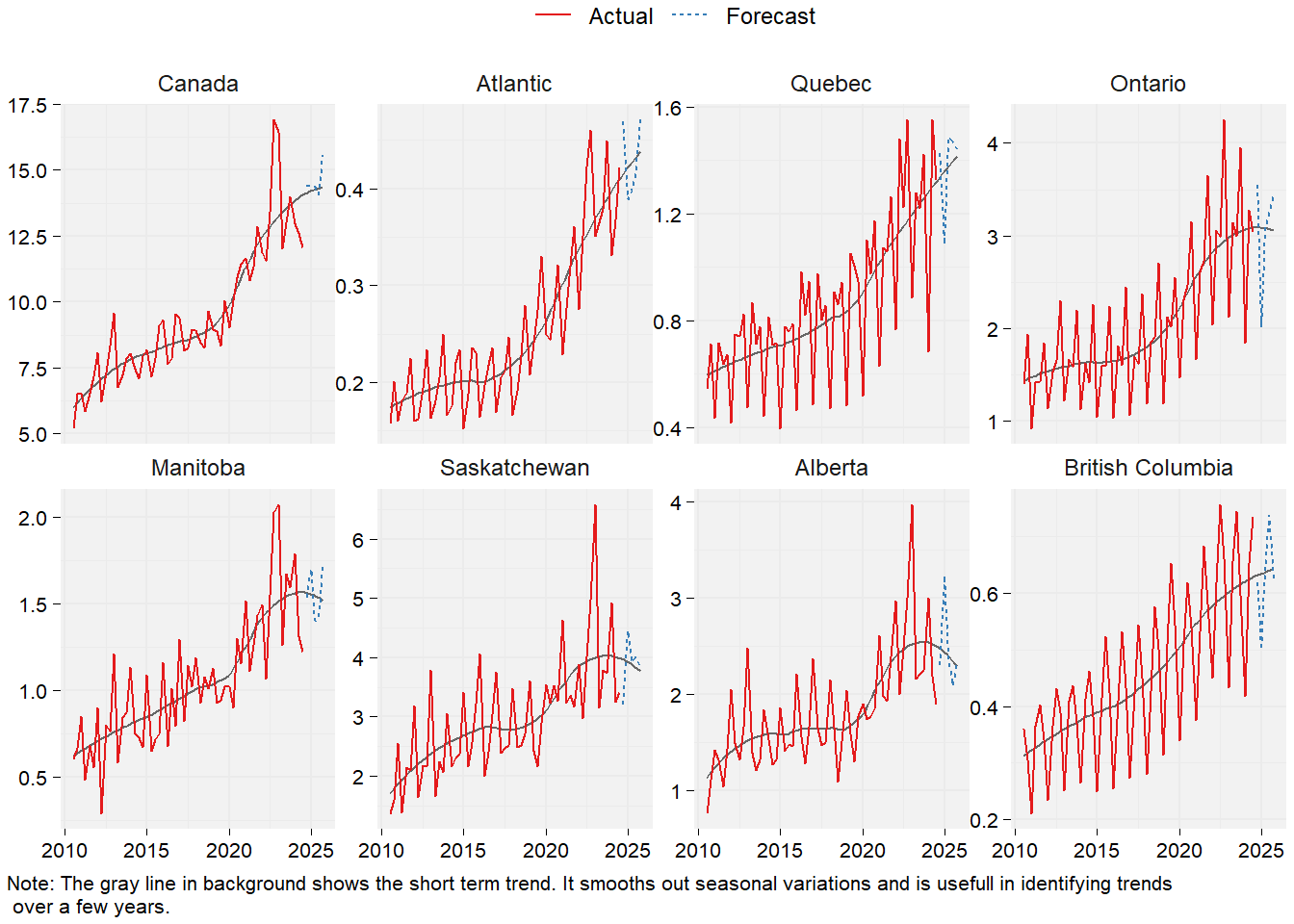

The quarterly farm cash receipts data are from Statistics Canada Farm cash receipts series. The most recent observations are for the third quarter of 2024.

Total crop cash receipts

Crop receipts are seasonal, in particular in provinces like British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec, where non-storable crops account for a greater share of receipts. Crop receipts in the Prairies provinces are mostly from grain and oilseeds, storable commodities, somewhat smoothing crop receipts as farmers sell them throughout the year.

Crop receipts have trended up between 2010 and 2020 in all provinces. However, since peaking in 2022, they have weakened and flattened in the Prairies provinces. Similarly, they have flattened in Ontario over the last five years. For other provinces, crop receipts have continued to trend up.

Figure 4: Quarterly total crop receipts (billion CAD)

Total livestock cash receipts

Growth in livestock receipts was weak in all provinces between 2010 and 2015, except for British Columbia. Growth has picked up since. Livestock cash receipts have trended up in recent years in all provinces and are expected to continue trending up in 2025.

Figure 5: Quarterly total livestock receipts (billion CAD)

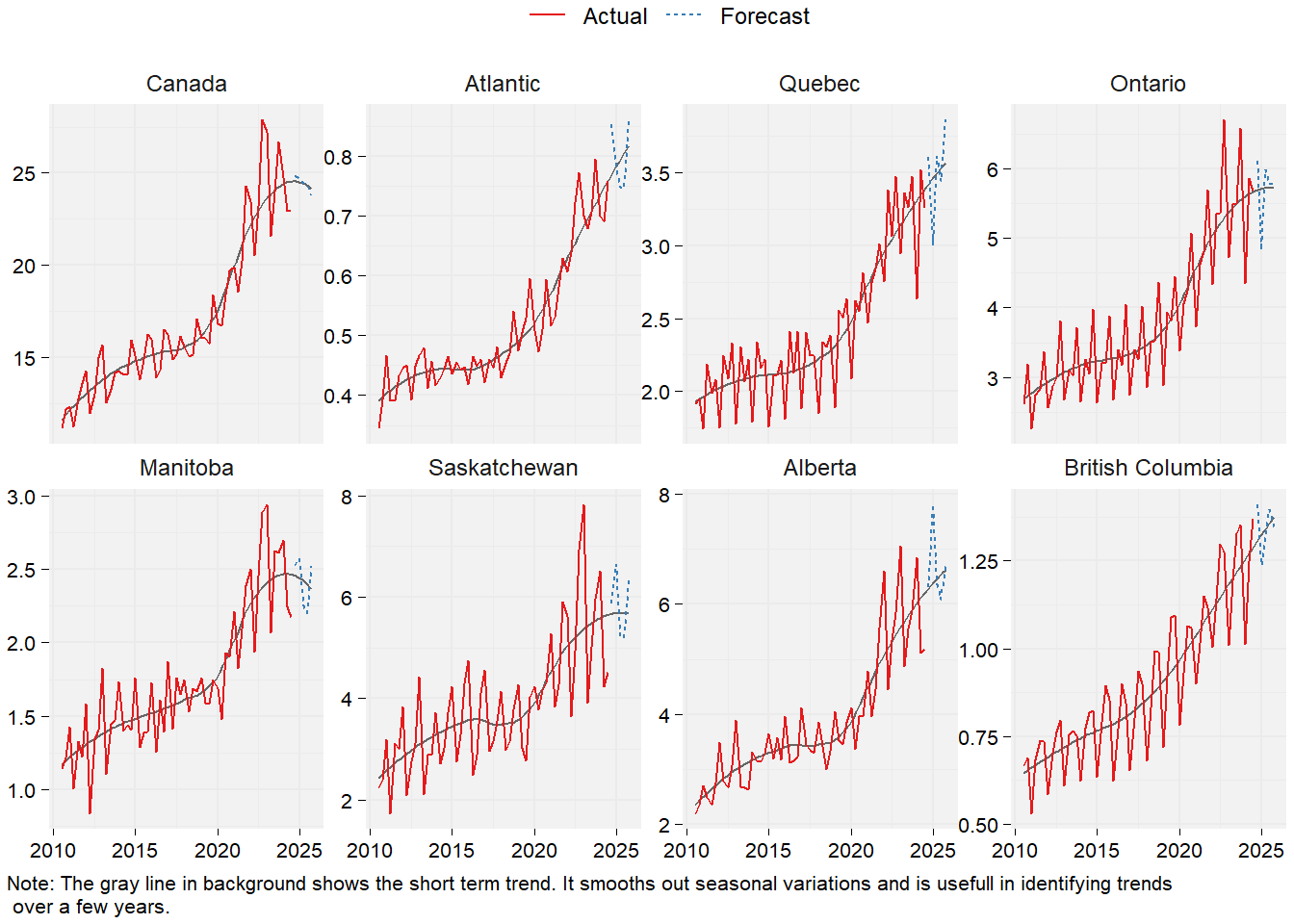

Total farm cash receipts

For total farm cash receipts, the trends depend on the relative sizes of crop and livestock receipts in each province.

Farm cash receipts have flattened and are not expected to grow in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Ontario. Cash receipts in these provinces more heavily depend on crops. In Alberta, it is the stength of the cattle sector that is pulling cash receipts up. In other provinces, total farm cash receipts are trending up and are expected to continue growing.

In total for Canada, farm cash receipts are stagnating following the trends in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Ontario, who together account for more than half of the total receipts.

Figure 6: Quarterly total receipts (billion CAD)

Are there farm recessions in Canada?

There is no short answer to that question, and nuances are necessary in a complete answer.

Given declining prices and revenues, the commodity crop sector is likely in a recession, and will continue to be in 2025 in all likelihood. Prices and revenues are generally strong in the livestock sector and should remain strong in 2025. However, this does not means that all types of livestock operations are doing well.

The farm sectors in Manitoba and Saskatchewan are likely in recession. The Ontario farm sector might also be in a recession but it is less severe because of more diversified farm revenues. The conclusion is similar for Alberta, who is seeing total farm cash receipts growing driven by its large cattle production. The farm economy appears more robust in other provinces

I haven’t mentioned input costs thus far, an important factor in the financial health of farms. Farm input price inflation has slowed down over the last two years and prices for some inputs, like fertilizer and fuel, have declined. Nonetheless, input prices continue to grow and against lower revenues in the commodity crop sector, it means increased financial stress to crop farms. Livestock farms are generally doing better as revenues are growing.

I do not have the data to evaluate the recent financial health of crop farms but the data above suggest it is declining. There are several programs available to Canadian farmers to cover production losses, increased input costs and market conditions. Generally, these programs are designed to cover losses from sudden shocks. They are not adapted to the current situation where commodity prices decline over an extended period of time, while input costs continue growing. If low crop prices continue, governments may wish to step in to keep too many farms from a dire outcome.